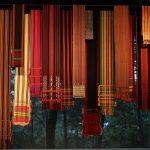

Weavers work with two sets of yarn-the warp and weft. The series of yarns that run lengthwise in a loom make up the warp. Woven in and out of the warp threads from one side to the other is another series of yarn called the weft. Through the mechanism of the loom, warp and weft interlock to produce cloth. The patterns, designs, and color combinations that add distinction to textiles are achieved through this interlacing of warp and weft in various permutations, from basic plain weave to elaborate forms like those enhanced by supplementary wefts.

In the traditional handwoven textiles of the Luzon Cordillera, warp and weft go beyond form and they create narratives of identity, social differentiation, political purpose, religious creed, and belief in the afterlife. The patterns, motifs, and color schemes in textiles are not mere embellishments but cultural signifiers whose functions are diverse. They may serve to distinguish one ethnic group from another. They may assume important roles in ritualistic and economic village activities and serve as markers in the various stages of the life cycle. They may constitute a form enactment in political undertakings like the Kalinga peace pact (bodong), or signify class standing as seen in the ritual and festal regalia of the Ifugao elite (kadangyan). In the past, some textiles were even used as forms of currency in economic transactions.

Like the warp and weft that interlock to produce cloth, the different tales told by Cordillera Textiles intersect to create singular representations of a people’s sense of themselves.