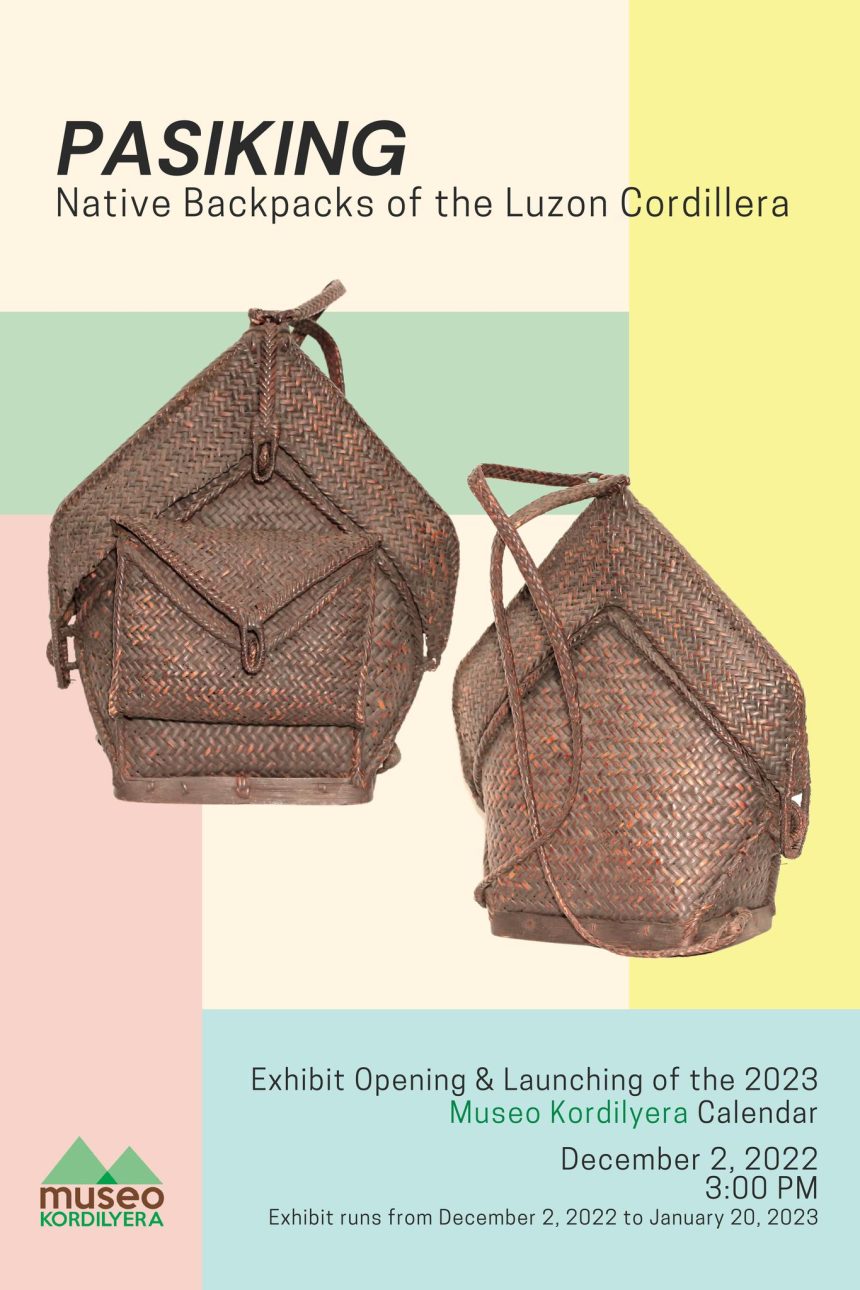

PASIKING

Native Backpacks of the Luzon Cordillera

Basketry is a time-honored tradition in the Northern Luzon Cordillera where the weaving of baskets from vegetable fibers is considered an essential skill among the natives of the region, from Apayao to Abra. Whether done for mundane activities or for special events, baskets are part and parcel of communal life, and their astounding variety serves as cultural signifiers that speak of the ethos of local communities.

Of the various types of baskets produced in the region, the most famous because it is the most ubiquitous is the native backpack known as pasiking. In places frequented by tourists, particularly in the city of Baguio, the pasiking is peddled everywhere, enthusiastically consumed by souvenir hunters and fans of ethnic chic. Little do these consumers know that most of the backpacks sold in tourist traps—mass-produced, mostly uninspired—have little in common with the backpacks patiently woven by native artisans who respect the requisites of craft.

Although the word pasiking has become a generic term for the native backpack, the backpacks of the Cordillera, whether utilitarian or ritualistic in purpose, come in various forms and styles; thus they have assumed different names in various contexts. The pasiking called inabnutan and fangao (Ifugao, Bontoc) is a hunter’s backpack also used as raincape because of its waterproof qualities. The takba (Bontoc, Kankana-ey) including the inabnutan (Ifugao) are ritual baskets used by ritual specialists (mambunong, mumbaki) in harvest, thanksgiving, and healing rites. In day-to-day living, the pasiking are much favored for storing belongings (e.g., personal accoutrements, mementos from home) and implements for long travels, and at times to carry food when working in the rice fields.

It is mostly the men who weave the baskets, which are usually made from bamboo, rattan, nito, and other local fibers. Different weaving techniques are employed: plaited, twined or coiled or a combination of these techniques. With the advent of modernity, the availability of ready-made bags and the prohibition in the use of scarce raw materials have somehow led to the decline of the manlalaga (basket weavers) in various communities. However, the resilience of these craftsmen has inspired them to innovate using new materials such as plastic conveyor belts from the mines. Old techniques are used, but new ones may also develop as weavers improvise, ensuring the continuity of ancient crafts.

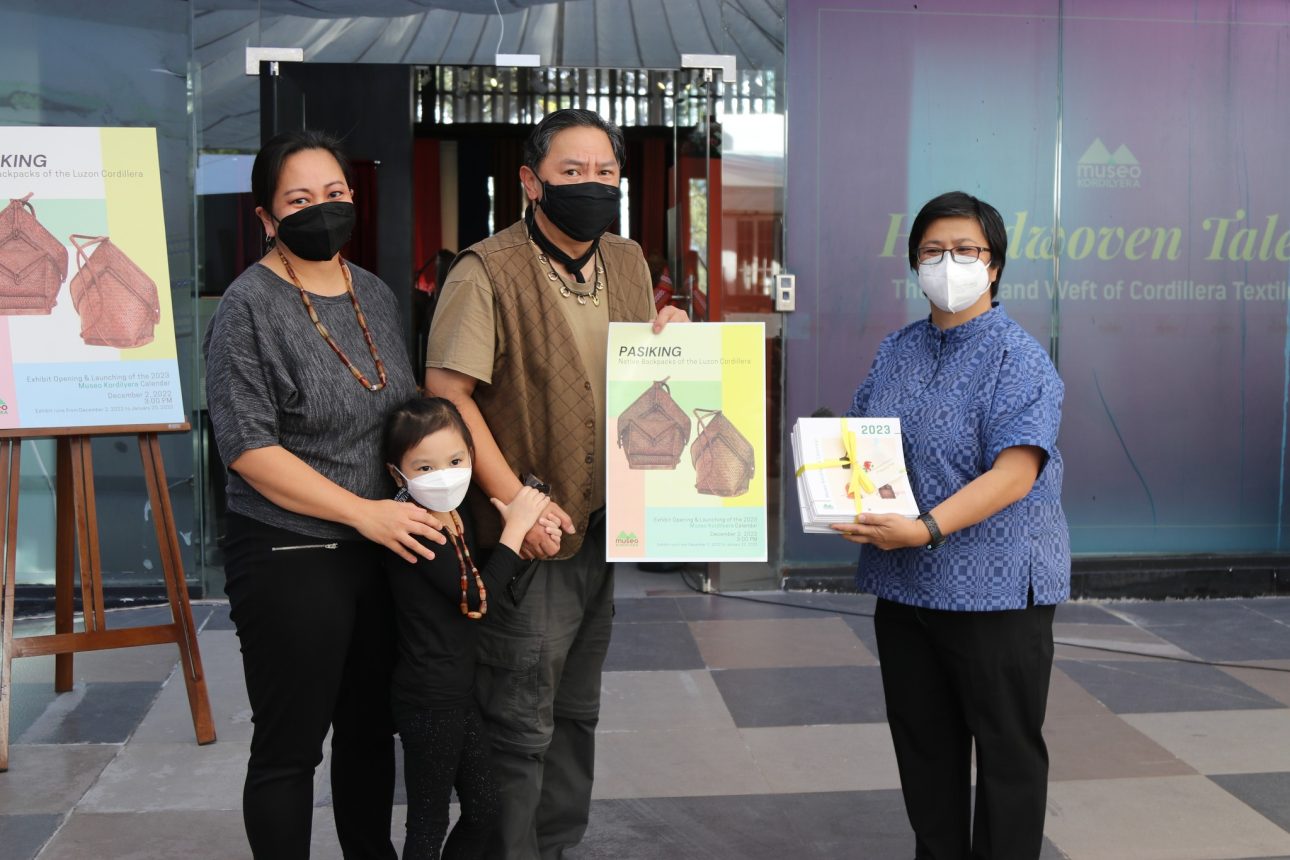

About the Pasiking Collection

The pasiking featured in this exhibit are from the Armand Voltaire and Maricel Cating Family Collection. A.V. Cating’s fascination with woven backpacks started when he was in college. He has conducted research on Cordillera material culture, and collected baskets from the region. Items from his extensive pasiking collection have been exhibited in “Eloquent Simplicity: In Wood and Fiber,” Yuchengco Museum, Makati (2012); “Carriers of Tradition: The Backpacks of the Northern Philippines,” Terganza Museum, San Francisco State University (2004), and Bencab Museum, Benguet (2014).